Body mechanics involve the coordinated effort of muscles, bones, and the nervous system to maintain balance, posture, and alignment during moving, transferring, and positioning patients. Proper body mechanics allows individuals to carry out activities without an excessive use of energy, and it helps prevent injuries for patients and health care providers (Perry, Potter & Ostendorf, 2018).

Elements of Body Mechanics

Body movement requires coordinated muscle activity and neurological integration. It involves the basic elements of body alignment (posture), balance, and coordinated movement. Body alignment and posture bring body parts into position to promote optimal balance and body function. When the body is well aligned, whether standing, sitting, or lying, the strain on the joints, muscles, tendons, and ligaments is minimized (WorkSafeBC, 2013).

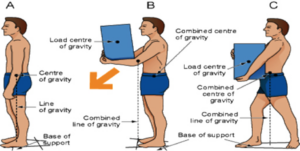

Body alignment is achieved by placing one body part in line with another body part in a vertical or horizontal line. Correct alignment contributes to body balance and decreases strain on musculoskeletal structures. Without this balance, the risk of falls and injuries increases. In the language of body mechanics, the centre of gravity is the centre of the weight of an object or person. A lower centre of gravity increases stability. This can be achieved by bending the knees and bringing the centre of gravity closer to the base of support, keeping the back straight. A wide base of support is the foundation for stability, and is achieved by placing feet a comfortable, shoulder-width distance apart. When a vertical line falls from the centre of gravity through the wide base of support, body balance is achieved. If the vertical line moves outside the base of support, the body will lose balance.

The diagram in Figure 3.2.1 demonstrates: (A) a well-aligned person whose balance is maintained and whose line of gravity falls within the base of support; (B) balance is not maintained when the line of gravity falls outside the base of support; and (C) balance is regained when the line of gravity falls within the base of support.

Principles of Body Mechanics

Table 3.1 describes the principles of body mechanics that should be applied during all patient-handling activities.

| Action | Principle | ||

| Assess the environment. | Assess the weight of the load before lifting, and determine if assistance is required. | ||

| Plan the move. | Plan the move; gather all supplies; and clear the area of obstacles. | ||

| Avoid stretching and twisting. | Avoid stretching, reaching, and twisting, which may place the line of gravity outside the base of support. | ||

| Ensure proper body stance. |

|

||

| Stand close to the object being moved. |

|

||

| Face direction of the movement. | Facing the direction of the movement prevents abnormal twisting of the spine. | ||

| Avoid lifting. |

|

||

| Work at waist level. |

|

||

| Reduce friction between surfaces. |

|

||

| Bend the knees. | Bending the knees maintains your centre of gravity and lets the strong muscles of your legs do the lifting. | ||

| Push the object rather than pull it, and maintain continuous movement. |

|

||

| Use assistive devices. | Use assistive devices (gait belt, slider boards, mechanical lifts) as required to position patients and transfer them from one surface to another. | ||

| Work with others. | The person with the heaviest load should coordinate all the effort of the others involved in the handling technique. |

(Data sources: Berman & Snyder, 2016; Perry et al., 2018; Registered Nursing, n.d.; WorkSafeBC, 2013)

Maintaining Proper Body Mechanics

- When standing, keep your feet about hip width apart (about 12 inches). This provides a strong base of support and balance for you to work.

- Always bend at your hips and knees when lifting or stooping, instead of bending at the waist and overextending your back.

- Use the larger and stronger muscles of your thighs, hips, shoulders, and upper arms while bending or lifting objects. This protects your back and smaller muscles from injury.

- Hold heavy objects close to your body when lifting or carrying them.

- Turn your entire body, including your head and legs toward the task you are doing, rather than twisting.

- Remember good posture. Keep your back and trunk straight and aligned with your hips and your head facing forward toward the direction you are working. This prevents twisting, which increases your risk of injury.

- Always raise the bed to waist height when working with a patient who is in bed, or making a bed. This prevents unnecessary bending of your back.

- When pushing, place one leg forward. When pulling, move one leg back. This provides you with a stronger and more stable base of support than if both legs were next to each other.

- Whenever possible, have another person help you with lifting, rolling, or moving patients.

- Have others help you with lifting or moving heavy objects.

- Do not perform tasks that will be physically dangerous to you, or for which you may not physically be capable.

- Keep in mind that when moving a patient, the path or direction in which you are moving must be clear of objects that could get in the way and cause potential injury.

- Always lock the brakes on the bed and wheelchair before transferring a patient. This prevents the bed or wheelchair from moving and causing potential injury to you or the patient.

Patient Handling Injury Prevention

Health care providers experience musculoskeletal injuries (MSI) when the physical demands of the job tasks exceed the physical capabilities of the worker, resulting in strain or sprain type injuries. Understanding the risk factors, the early signs, and symptoms of injury, and work procedures that control or minimize the risks will help keep you, the HCA, safer at work.

The role of an HCA is hard work. You may know many caregivers who were injured during work; some never returning to the job they love and are well trained to perform. The kind of tasks required in caring for clients often make it difficult to see another way of providing needed care while being careful with your body. However, it is important for you to remain healthy and safe at work.

Moving and assisting clients is not like moving boxes — which have convenient handles and behave predictably. When assisting a client during care routines, HCAs develop a relationship with that person, which can interfere with your ability to be objective about the risks involved. Being able to quickly and accurately assess the client’s ability to participate, being mindful of the risk factors, knowing the available transfer options and equipment, and being aware of your own abilities helps to reduce the likelihood and consequences of injury. The prevention of MSIs often requires changing work practice and redesigning job tasks.

Being a healthcare provider puts you at high risk of injury. As a result, employers place a high priority on maintaining a safe work environment for employees while providing quality client care. For example, employers may implement “no manual lifting” policies and programs to keep everyone safe. The no-lift model of care approach seeks to reduce unnecessary risk, and introduces and promotes safer ways of moving and assisting clients while providing high quality care. A program for the prevention of patient handling injuries should have management commitment and support, proper and safe patient handling equipment, equipment maintenance, employee training, advanced training for resource staff, and offer a shared ownership approach to safe patient handling (Interior Health, 2011; Workers Compensation BC, 2008).

Musculo-Skeletal Injury (MSI)

(MSI) has been defined as an injury or disorder of the muscles, tendons, ligaments, joints, nerves, blood vessels or related soft tissue, including a sprain, strain, and inflammation that may be caused or aggravated by work (Workers’ Compensation Board of British Columbia, 2009).

Workers may notice pain, numbness, tingling, or weakness while on the job.

Sometimes pain is just a part of a person’s everyday life, and can be ignored. Other times, it can be a result of an injury or disease. To decrease the chances of injury or disease, it may be necessary to reduce exposures to physical movements at work that have the potential to place you, the HCA, at risk of injury (like strain) or disease (like tendinitis or carpal tunnel syndrome). It is important to note that each individual’s response to a physical exposure is different. The human body was designed to be active, so eliminating all physical activity is also unhealthy (Workers’ Compensation Board of British Columbia, 2009).

It is important for you and your employer to recognize the signs and symptoms that could indicate an MSI. Signs that can be observed include swelling, redness, and/or difficulty moving a particular body part. Symptoms that can be felt but not observed include numbness, tingling, and/or pain. Signs and symptoms of MSI may appear suddenly — from a single incident, for example — or appear gradually, over a longer period from repetitive movements. If you are experiencing signs or symptoms of MSI, inform your supervisor and report to the first aid attendant (if there is one), or see a healthcare provider. An MSI may be treated more effectively if it is discovered and reported early (Workers’ Compensation Board of British Columbia, 2009).

Potential Health Effects

An MSI can affect your ability to perform tasks at work and at home. Early signs or symptoms of MSIs can progress into conditions such as the following, which can have long-term effects:

- Muscle strains to the neck, back, shoulders, or legs

- Tendinitis (swelling of a tendon, which is a band of tissue that attaches muscle to bone)

- Carpal tunnel syndrome (pressure on a nerve in the wrist, resulting in numbness, tingling, pain, or weakness in the hand, wrist, or forearm)

Such effects generally occur due to the physical demands of doing a task. Tasks include force (lifting, pulling, or gripping an object); repetition (lack of rest or variation in muscle use, or when new to the task); work posture (awkward position, reaching overhead, or twisting); and local contact stress (tools or edges digging into the hand or wrist). The amount of risk from these effects depends on how long and how much you do the task in a given day over time.

Example Task:

An HCA repeatedly bends over low positioned beds to give care.

Table 3.2.2 lists risk factors that contribute to MSI.

|

Factor |

Special Information |

| Ergonomic Risk Factors | Force: Lifting, lowering, carrying, pushing, pulling, and grip all involve force. Strong forces and light forces present risk for MSI.

Repetition: Refers to using the same group of muscles to complete a task over and over, with little time for muscles to recover. Work posture: The position of different parts of the body, particularly awkward positions, can exert force on the muscles and bones, which causes strain. When a joint bends excessively or awkwardly, or outside its range of motion, MSI can occur. This also includes static postures. Workers need to change their body posture and move about periodically. Local contact stress: Refers to when hard or sharp objects come into contact with the skin, and the nerves and tissues become damaged by pressure. |

| Individual Risk Factors | Poor work practice; poor overall health (smoking, drinking alcohol, and obesity); poor rest and recovery; poor fitness, hydration, and nutrition. |

(Data sources: Perry et al., 2018; WorkSafeBC, 2008; WorkSafeBC, 2013)

MSI Prevention

As the saying goes, “Prevention is the best medicine.” As a healthcare worker, you are in the best position to understand the demands of the job, recognize the risks, and prevent MSI. If you experience or see unsafe working conditions or equipment, you should report them immediately to your supervisor, so changes can be made to eliminate or minimize risk.

MSI Treatment

If you experience any strain or other injury, report it as soon as you are able. Treatment will vary according to the type of MSI. Treatment can include the application of cold or heat, medication, physical therapy, and even surgery. An MSI may be treated more effectively if it is discovered and reported early. (Workers’ Compensation Board of British Columbia, 2009)

- Healthcare employers have a responsibility to provide a safe workplace for their staff, strive for a healthy work environment, and recruit and retain adequate numbers of professionally qualified staff.

- Research over the last 30 years has documented the cumulative risk of lifting and transferring patients to nursing personnel: Interventions based solely on techniques or education has no impact on working practices or injury rates.

- Risk of injury to staff is cumulative: Identified client handling concerns must be promptly addressed to avoid increasing the likelihood and consequences of staff or client injury.

- A standard client risk assessment that identifies the client’s ability to participate in their care is important. Swift and open communication of the plan, and any adjustment required due to the client’s changing ability is essential.

- Assistive equipment and transfer devices need to be available and in good working function. They should be used and promoted as a way to improve safety and function in acute, long-term care, and home settings.

- It is essential to share decision-making within the team on the most appropriate ways of moving and assisting clients, to ensure a consistent approach by all care providers. All staff interacting with a client needs to know how to assess the client’s ability to participate in their care, and have the skills to make choices that protect the safety of the client and themselves (Interior Health Authority, 2011; Workers Compensation BC, 2008).

The way in which body parts (head, trunk arms and legs) are positioned in relation to one another.

The point in the body in which weight is evenly distributed or balanced on either side.

standing with feet shoulder width apart to improve stability

ability to maintain the line of gravity within a base of support